Principles 14- Narration: The Art of Telling Back: “As knowledge is not assimilated until it is reproduced, children should 'tell back' after a single reading or hearing: or should write on some part of what they have read.” (Vol. 6, xxix)

This past January, it snowed seven inches on our Tennessee mountain. Snow is a novelty for us and my kids were thrilled. We cancelled school and spent the entire day outside. We drank a gallon of hot chocolate, and I made chicken noodle soup. It was dreamy in every way. Afterwards, my kids could not stop talking about all they’d done, what they’d discovered about snow, and how many animal tracks they’d found. They just had to tell anyone who would listen about their exciting day. In short, they narrated their snow day and thereby added the experience to our family’s collective memory. It was a natural response to the exciting experience.

What my kids did in telling about their snow day is a human response. Sharing the experience through recalling what happened also helped them to relive their excitement with the rest of us and cemented those glorious moments into their memories. That’s why narration is such a powerful tool because it uses the child's natural inclination to tell back to help them remember what they’ve learned.

What is Narration?

Narration is the fastest way to learn new ideas because we have to recall and organize them in order to share them. That’s why narrating a passage makes it easier for us to retain the information. Instead of passively listening to a story, when a narration is required, the mind is challenged to adapt and synthesize the information in order to tell it back to someone else. In addition, as the narrator works out the narration, he begins to make connections with other ideas as he tries to recall what he’s learned. He might make a comparison or draw out something that was said that stuck out to him, these are all parts of the ways the narrator makes the information his own.

What Narration is Not

Narration is not memorization. Children are not just regurgitating what they’ve heard or read, they must tell back in their own words and recall the story in order, but with their own connections. We want their narration to be freely given because we are educating freemen to think freely.

Narration is not a time to drill a child for specific facts related to a passage. Children can easily feel our anxiety when we try to pepper them with questions about the reading. Instead, we are leading them into a relationship with the ideas and helping them see how to connect one event to another or to help them have sympathy or cultivate curiosity in them about events or people presented in a story.

Finally, narration is not a mechanical skill but a relational skill. When a child connects with ideas from a story, his human response is to tell back and share what happened. Just like the events of the snow day, the events in a story will shape the child and make an impression on him. Narration is a relational art that aids our work as educators to put the work of education on the child with the teacher as a guide.

We’ve looked at what narration is and what it is not, but how do we help our children cultivate this skill?

How to Prepare a Child to Give a Narration

A big mistake many Charlotte Mason homeschoolers make is reading a passage to a child without setting him up or preparing him for the work of giving a narration. Narration is a skill, not just an instinct. We can guide children in learning how to do it well, rather than relying solely on their natural ability. Now that we understand the power of narration, how do we set our children up for success?

Connect the Child’s Knowledge to New Ideas

Before reading, briefly review the previous lesson and explain how today’s reading builds on it. This could be as simple as asking for a narration of the last lesson.Set Up the New Lesson

Help the child engage with the reading by introducing key elements:

Write important names or words on the board.

Show a map if places are mentioned.

Display a painting or image of a historical figure.

All or just one of these can be used - the goal is to move children from what they already know and into new ideas.

Set the Expectation for Narration

Let the child know they will be asked to tell back the story. This simple step turns on their mind as an active learner rather than a passive listener.Read the Passage

Either read aloud or have the child read independently. If they are reading on their own, ensure they understand the narration expectation.

This entire set up can just be a matter of saying three sentences:

“Where did we end our story last time?”

“Let’s look at the map and see where these events take place.” (I always like to point out where we are and where the people we are talking about lived to give context on the map.)

“Make sure you listen carefully because I will ask you to tell me what happened in the story.”

Once you set up your reading in this way, your child will be primed to connect with the story. This setup will help your child cultivate the habit of attention because, as we will see in the next principle, that’s essential to giving a successful narration.

Narration Variations

Once you’re comfortable with oral narration, you’ll start to see that narration can take many forms beyond simply telling back. Depending on the subject, children can engage with ideas in creative and meaningful ways:

Knowledge of Man (History, Literature, Biography)

Instead of just retelling the story, children can:

Act out a scene – Younger children might reenact a historical moment or a fable with toys.

Draw a picture – A child could illustrate a key event or character from the reading.

Write a letter– Have them write a letter from one historical figure to another, expressing their perspective.

Compare events– Encourage older students to connect historical events across time periods (e.g., comparing the American and French Revolutions).

Knowledge of the Universe (Science, Geography, Nature Study)

Hands-on and visual narration works well here:

Draw a diagram– Instead of summarizing a lesson on the water cycle, a child could draw and label it.

Conduct an experiment– After reading about magnetism, they could demonstrate it with a hands-on experiment and explain their findings.

Keep a nature journal– Observing, sketching, and describing birds, plants, or weather patterns reinforces learning.

(Would you like more inspiration for keeping a nature journal? Try my 5-Day Nature Journal Challenge. You will receive a new nature journal prompt each day starting today! Click here to grab yours.)

Knowledge of God (Bible, Theology, Character Formation)

Narration in here helps internalize ideas:

Retell a Bible story– Encourage younger children to share what they remember in their own words.

Illustrate a scene – Drawing David and Goliath or Jesus calming the storm deepens engagement.

Pray and apply – For habit training, discussing a biblical lesson and practicing virtues (e.g., patience, kindness) makes learning real.

Just as my children couldn’t help but tell back their snow day adventure, narration allows them to absorb and share what they learn in a meaningful way. It transforms fleeting moments and ideas into something lasting, something they can return to again and again. John Greenleaf Whittier captures this beautifully in his poem Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl , where he recalls a childhood winter storm, bringing the past to life through vivid storytelling. In the same way, narration helps our children make knowledge their own, preserving it like a cherished memory:

"Shut in from all the world without,

We sat the clean-winged hearth about,

Content to let the north-wind roar

In baffled rage at pane and door,

While the red logs before us beat

The frost-line back with tropic heat;"

Through narration, we give our children the gift of truly knowing—of taking what they’ve seen, heard, and read and making it part of who they are. And just like the warmth of a remembered snow day, the stories and ideas they narrate will help them make deeper connections as they go through their school years.

“The simplest way of dealing with a paragraph or a chapter is to require the child to narrate its contents after a single attentive reading,––one reading, however slow, should be made a condition; for we are all too apt to make sure we shall have another opportunity of finding out 'what 'tis all about.'”(Vol 3, p. 179)

(See Sample narrations below for ages 6-15.)

**If you want to be effective with your Nature Study work, check out my Nature Study Hacking Guides at www.howeverimperfectly.com. Learn how to get outside and use those lovely nature journals.**

20 Principles of a Liberating Education:

#2 The Good and Evil Nature of Children

#3 Parents are in Charge and Children Must Obey

#4 Limits to Our Authority as Parents and Educators

#5 Education is an Atmosphere, a Discipline, a Life| a primer

#9 Feeding the Hungry Mind

#10 From Bucket Heads to Bright Minds| The True Role of Teacher & Learner

#11 Drop the Timeline Song| Education is Cultivating Wisdom Through Nourishing Ideas

#13 The Curriculum i.e. The Living Library

#14 The Art of Narration (You are Here)

Bibliography for further reading:

Know and Tell by Karen Glass

Start Here, a Journey through Mason’s 20 Principles by Brandy Vencel

Philosophy of Education by Charlotte Mason

The Mind at Work (PNEU article)

Sample Narrations:

Audio 6-year-old girl oral narration from The Cat and Mouse from The Yellow Fairy Book by Andrew Lang:

Audio 8-year-old girl oral narration from Diamonds and Pearls from The Blue Fairy Book by Andrew Lang.

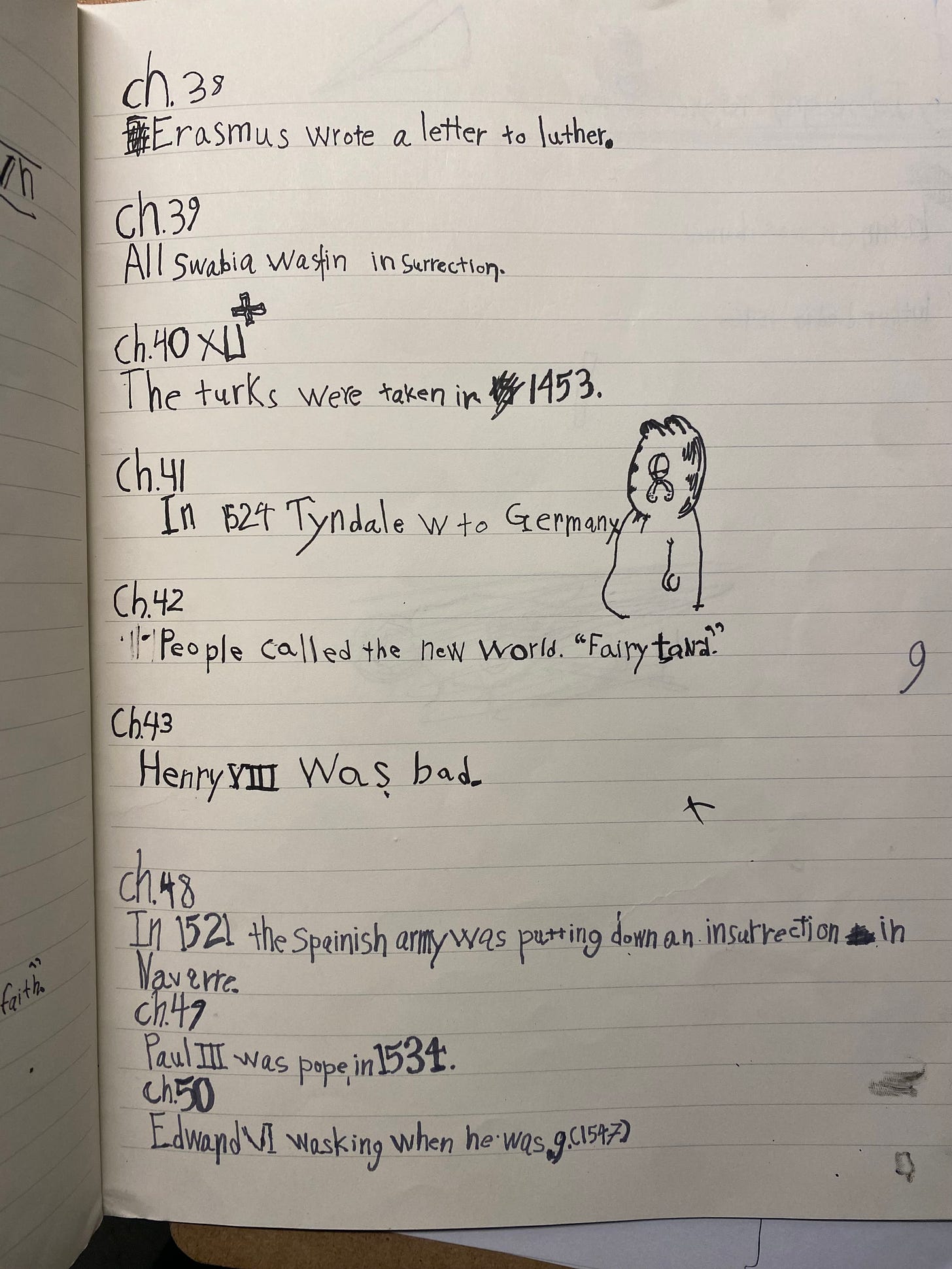

Written narration sample from 10-Year-old boy struggling writer from The Story of the Renaissance and Reformation by Christine Miller. The assignment was to write one topic sentence about each chapter read. (He read three chapters each week from this book independently.)

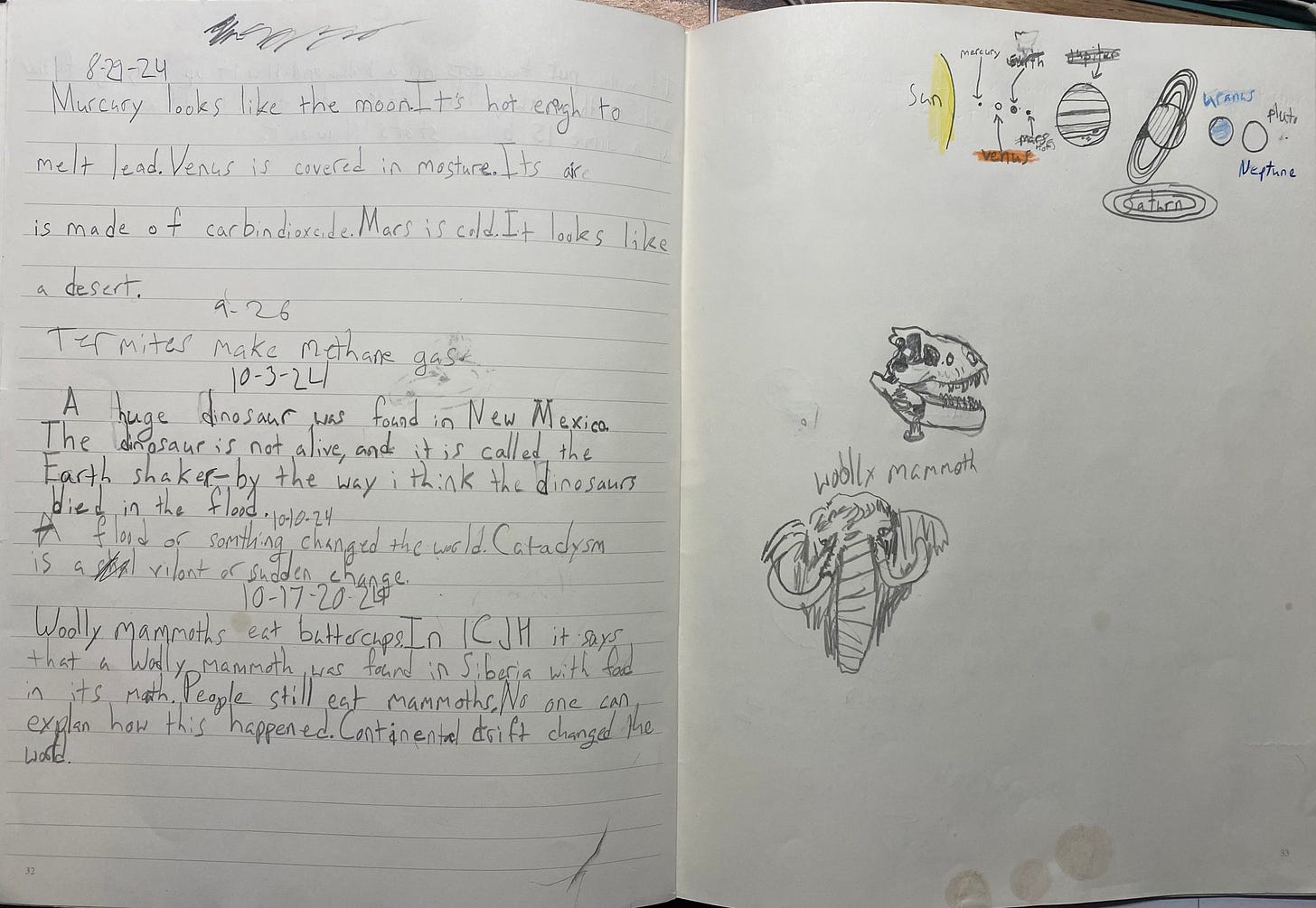

Written narration and diagrams from 11-year-old boy science reading: It Couldn’t Just Happen by Lawrence Richards. The assignment was to write a narration from the reading and draw diagrams when it was helpful.

Written narration from 13-year-old boy history reading using This Country of Ours by H.E. Marshall. The assignment was to write a narration about what happened in the chapter and write questions related to the chapter. We used the questions in a quiz game with a group of four boys

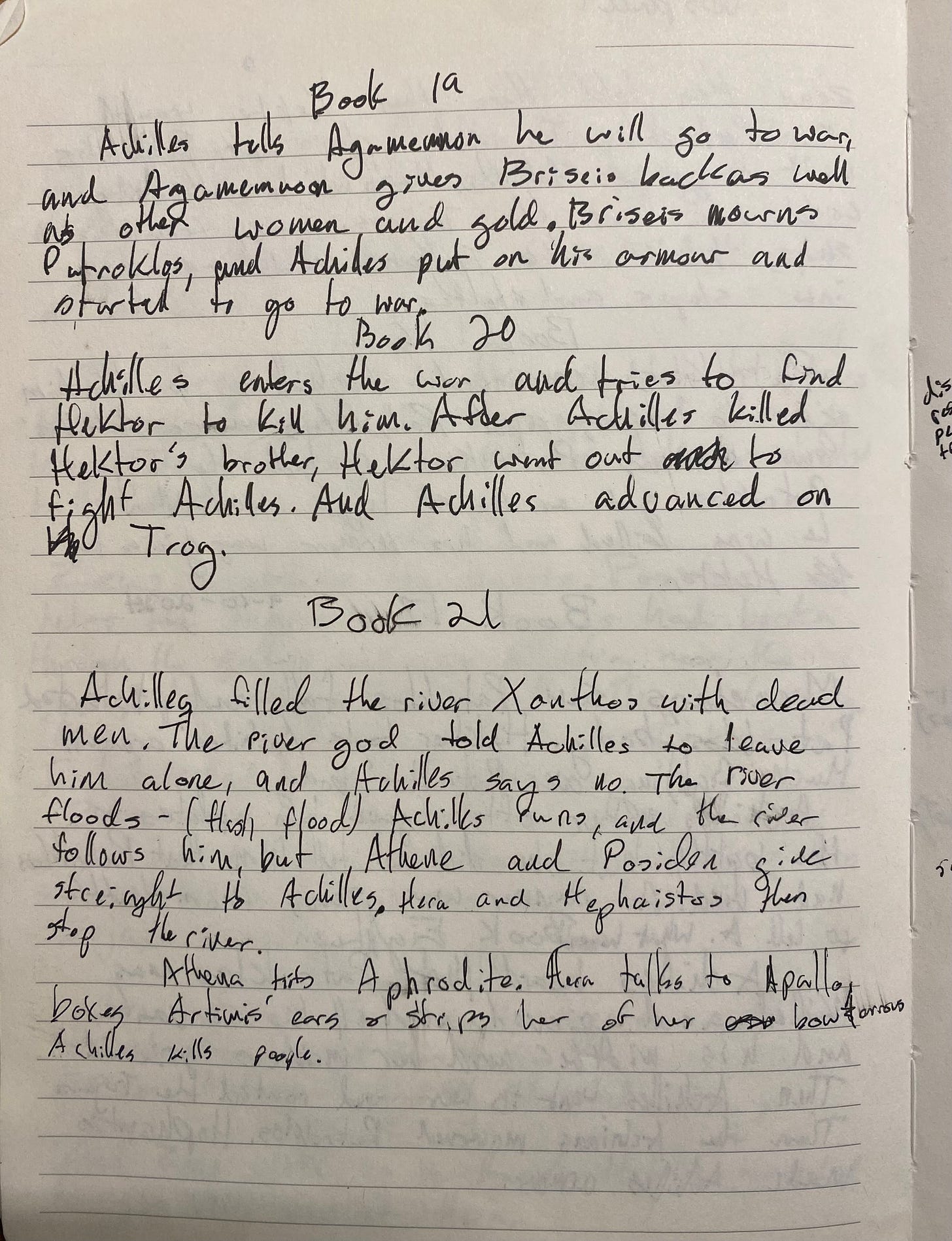

Sample narration from 15-year-old girl literature reading from the Odyssey by Homer. This narration offered the foundational reading for the literature essay that follows.

Sample literature essay from 15-year-old girl using the narrations from the Iliad to complete the assignment. This assignment took about six weeks to complete and was presented at a co-op function at the end of the semester. The process including: thesis, outline, citations, first draft etc. were broken into individual assignments submitted to the tutor for feedback and guidance.

Share this post