Principle #19: Therefore, children should be taught, as they become mature enough to understand such teaching, that the chief responsibility which rests on them as persons is the acceptance or rejection of ideas. To help them in this choice we give them principles of conduct, and a wide range of the knowledge fitted to them. These principles should save children from some of the loose thinking and heedless action which cause most of us to live at a lower level than we need.

As a teen I spent a week with my aunt and uncle one summer in their Southern Living style home. Each detail of her home was lovely, welcoming, and the picture of Southern hospitality. My cousin, who was my age, was the only child living at home. My aunt was a home decorator by trade, so I always expected it to be beautiful and well decorated. As I think back, there’s one detail of the home design and domestic splendor that I remember: the linen closet. (I know! You want to hear about her kitchen windows that look over the garden and her feather-stuffed sofas, but no. We are opening her cupboards!) The linen closet surprised me by being pretty and organized. When I opened the closet to grab my towels, I found plush sage green matching towels neatly stacked and perfectly folded. The bed linens were folded and placed inside of their pillow cases and then stacked smoothly. Everything was at the perfect height and the order itself protested against shoving a towel in willy-nilly without carefully folding it to match its shelf mates. I thought of her linen closet the other day when I was stuffing our towels and sheets into our linen closet. How did she make the linens lay so neatly in the closet? How did she fold her fitted sheets? Why do I allow my linen closet to stay so unkempt? (Matching colors do make a difference but are not always practical when hand-me-downs are, well, free.) What does that say about me? What does her orderly linen closet say about her?

To be fair, my aunt had three children and I have seven. Her children went to school and were gone all day, whereas mine are home. All. Day. Everyday. Her work was to decorate the homes of “high society” clients, mine is to be jack of all trades in my own home. But what I want to know is: what principles did she embrace automatically that led her to keep an orderly linen closet instead of a messy one? It was beautiful. It was hospitable. When I opened it 1. I could find the towels I needed. 2. The order was striking enough for me to remember it 30 years later. She was clearly guided by good principles that cherish order and beauty.

Just as my aunt’s linen closet didn’t happen by accident because she was driven by principles of order and beauty, so too our children need intentional instruction to learn good principles that shape their conduct.

Principles of Conduct Guide Us (towards goodness or evil)

Good principles are the heart and motive that drive our conduct. They give us the filter we need to make decisions with grace and confidence. They don’t demand or intrude. Bad principles are loud and urgent. They impose order instead of inviting it. They trip us up and keep us from living, as Mason points out, “at a lower level than we need.”

With this 19th principle, Mason reminds us that children need to be given good principles of conduct. We don’t want to leave this aspect of their education to chance. We can and ought to teach them principles that will help them think and act wisely. This approach is very different from my laissez faire approach to linen closet organization. My guiding principle for the linen closet has more to do with function and whether or not we can find anything than it does about order and beauty. I tend to get stuck in the drudgery of the laundry and dishes without remembering the importance of the work I’m doing. G.K. Chesterton gives us some good principles about our domestic work to help us lift our eyes to see the truth. He says,

"[W]hen people begin to talk about this domestic duty as […] trivial and dreary, I simply give up the question. For I cannot with the utmost energy of imagination conceive what they mean. When domesticity, for instance, is called drudgery, all the difficulty arises from a double meaning in the word. If drudgery only means dreadfully hard work, I admit the woman drudges in the home, as a man might drudge [at his work]. But if it means that the hard work is more heavy because it is trifling, colorless and of small import to the soul, then as I say, I give it up; I do not know what the words mean…. I can understand how this might exhaust the mind, but I cannot imagine how it could narrow it. How can it be a large career to tell other people's children [arithmetic], and a small career to tell one's own children about the universe? How can it be broad to be the same thing to everyone, and narrow to be everything to someone? No; a woman's function is laborious, but because it is gigantic, not because it is minute. I will pity Mrs. Jones for the hugeness of her task; I will never pity her for its smallness." (Emancipation of Domesticity, G.K. Chesterton)

Chesterton sees how big and meaningful our work is when we think that it’s small and pointless. What I’ve found is that if I see my work as small then my kids mirror my attitude. They think their chores and household tasks are small and we all become grumpy about our work. But this is because we don’t see them in the right way. We need to be fed with the right ideas about who we are and whose we are and what we are here for to help us do our work with dignity, grace, and gratitude. This is why our imaginations need to be fed so that we can see what virtue looks like in action.

Stories That Nourish the Soul

It’s difficult (or perhaps impossible) to understand how to act and be virtuous without an embodied example for us to imitate. We need to be able to see what virtue looks like in our mind's eye in order to live virtuously. We are, after all, mimics. I have often pictured Ma Ingalls in The Little House on the Prairie preparing supper in the middle of the prairie. She maintains her traditions and civilizing habits even in the middle of nowhere. Her principles carry her through many hardships and allow her to maintain her dignity when struggling through a pioneer’s life. I am able to see her virtue in the midst of challenges, and I’m strengthened (and convicted) to fortify myself for my own work. This is how stories work. They help us see virtue lived out. Which is what Mason wants us to see with this 19th principle: children need to be taught how to make good choices because this knowledge allows them to live in a way that honors their dignity.

Children need to be given tools to choose how to make good decisions. We aren’t reproducing machines, we are nurturing souls. These tools are “principles of conduct.” That’s what they need. But how they get those principles of conduct is with “a wide range of knowledge fitted to [those principles].” This “wide range of knowledge” comes from stories and lived experiences. Stories like The Little House on the Prairie help give us insight into human behavior and human nature. The story allows us to gain experience without having to live through each story ourselves. Fairy tales and myths fertilize the soil of the mind because they allow children to clearly see goodness and evil played out in a story. These stories show the interplay of the spiritual world and the physical world in a way that is impossible to see without the imagination. These stories help us to see the spiritual battle we are engaged in—the fight for the human soul. We want to fortify our children for this battle. Stories help to give them fertile ground soil that enables us to see the spiritual battle. But we have a difficult time seeing.

Our sight of spiritual things is limited because we live in the “information age.” We value information but have forgotten the importance of the imagination. We are analytical and literal. We love our theology and our science but we’ve neglected our biblical symbolism and our connection to nature. This has caused us to miss the poetic knowledge that allows our imaginations to thrive and inform our intellect. Without a cultivated imagination it’s difficult to read the Great Books and be nourished by them. Which is why it’s important to offer our children many great books.

The classics in children’s literature offer the best ideas and give our children’s imaginations plenty of nourishment. Classics should be preferred over modern books written after 1968 because modern books tend to focus on emotions and usually have an agenda. Classic children’s books have stood the test of time and deal with the transcendentals—those great ideas that are true for all men in all times. It is through these great ideas that our children come in living touch with virtue so that they can become intimately familiar with the true, good, and beautiful. This foundation in books gives them a fertile imagination so that they can read the classics once they get into high school. If they don’t have this foundation they become like many students attending elite colleges, who can’t read books at all. Or worse, they will read them and not be able to draw any nourishment from them

Principles in Education Matter to the soul of the child

There was an article in The Atlantic about Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books. Students in high school are no longer being required to read whole books cover-to-cover. Read an excerpt or a poem here or there, sure, but a whole book? It’s not as common. Why does this matter and what does it say about our society that we don’t require children to read whole books and that our elite college students are overwhelmed by the task? It shows, as Brandy Vencel points out, that our cultural soil is depleted. Homeschooling and classical education will help to reclaim what we’ve lost. That is done through giving our children vital knowledge through reading classic books. (I do insist on classic books and will argue that a high school education ought to involve a survey of the great books.) We give them these great books early and often so our children have a fertile imagination where virtue and good principles can flourish.

So, here we are with our messy linen closets and piles of books. We want our children to choose what is good and turn from what is evil. Teaching children in this way is less about rules that feel restrictive and more about the power of a story to inspire true freedom. They, like us, don’t see past the work at hand, they get discouraged and feel that their work is mundane and without any real point. But, like Chesterton said, “I don’t know what the words mean.” Just as it is a gigantic task to raise and educate children, the work our children do each day has value. The stories they read faithfully, the chores they do with heroic pride, the math lesson they tackle when the battle seems to be lost, form them into the man and woman they will become. There is nothing lost in the small tasks of the day. Each story read, each word spoken, each chore completed is helping them work out good (or bad) principles of conduct so that they can live at a level that honors the dignity they have as image bearers.

We don’t simply want to have tidy linen closets; we want to love order and beauty enough to be vigilant to fight against the pull towards chaos. The principle is what drives us- not the formula, the function, or the practical point. We are created to love and that must be pulling us towards connection and relationship. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry points out in his book The Little Prince, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.” We must have principles that dictate both how and why the work gets done (or doesn’t).

Good principles of conduct ought to guide children toward connections and relationships that honor their dignity as persons and raise them to live in such a way that is fit for image bearers of God. And of course, that leads us into our last principle, which we will look at in two weeks. See you then.

**If you want to be effective with your Nature Study work, join the Screen Free Kids Get Outside Challenge. Head over to HoweverImperfectly.com/ScreenFreeChallenge to download your free packet!**

Reflection Questions:

1. What principles of conduct are currently shaping my work as a mother and home educator? Are they intentional, or have they developed by default?

2. How do my principles impact my children’s attitudes in good ways? In bad ways?

3. What is one area I see bad principles affecting our home life? What scripture passages can help us redirect? What stories or habits could help us here? How would the atmosphere of our home and our attitudes help support us in this effort to root out a bad principle?

4. What stories have given me a good picture of the mother I want to be? What stories give our family a picture of the virtues we need to cultivate at this time?

5. Reflect and pray. Spend time asking the Lord to show you what principles are causing your family to live “at a lower level than we need.” Then consider what books you are currently reading with your children that could support you and inspire higher living. (Sometimes it’s just a matter of looking for virtue and vices in our stories and asking God to reveal Himself to us that helps us learn and grow with our children.

20 Principles of a Liberating Education:

#2 The Good and Evil Nature of Children

#3 Parents are in Charge and Children Must Obey

#4 Limits to Our Authority as Parents and Educators

#5 Education is an Atmosphere, a Discipline, a Life| a primer

#9 Feeding the Hungry Mind

#10 From Bucket Heads to Bright Minds| The True Role of Teacher & Learner

#11 Drop the Timeline Song| Education is Cultivating Wisdom Through Nourishing Ideas

#13 The Curriculum i.e. The Living Library

#16a and 17 The Way of the Will

#16b and #18 The Way of Reason

#19 Principles of Conduct (You are here)

Bibliography for further reading

Books that will help you grasp the 19th principles more deeply:

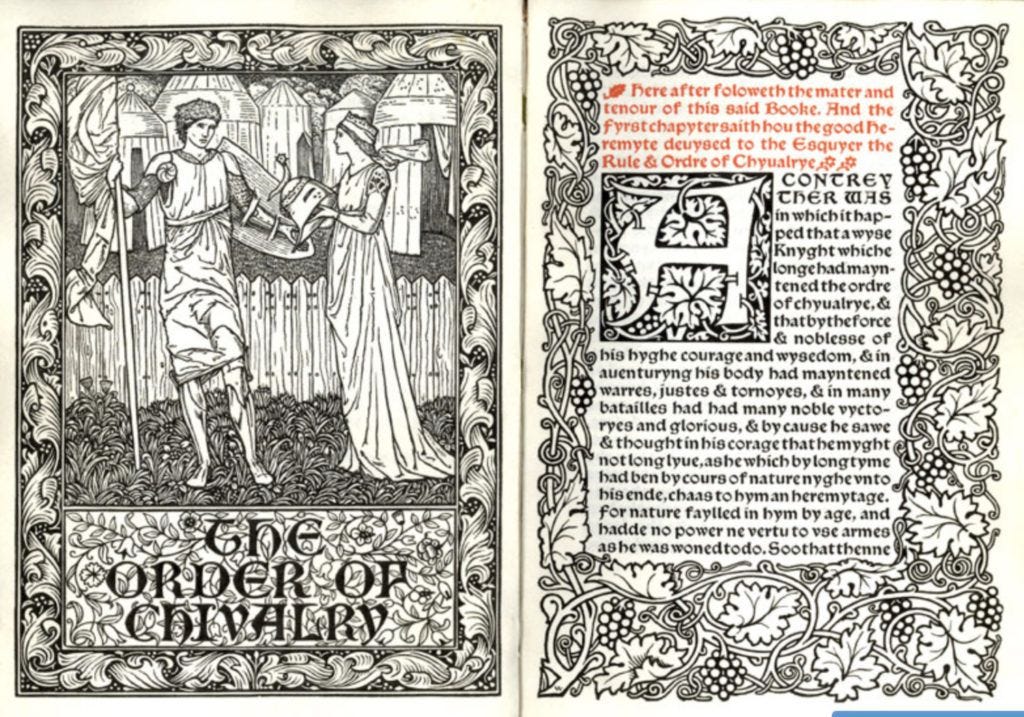

The Book of the Order of Chivalry by Ramon Llull (Author), Noel Fallows (Translator)

The Whole Brained Child by Daniel J. Siegel M.D. and Tina Payne Bryson

Heartfelt Discipline: Following God's Path of Life to the Heart of Your Child Paperback by Clay Clarkson

Laying Down the Rails by Simply Charlotte Mason (This book explains the habits and gives excerpts of Mason’s own words on each habit to be cultivated)

Laying Down the Rails for Children by Simply Charlotte Mason (This book has lessons on habit training to do with your family)

Books about Charlotte Mason’s Philosophy:

Know and Tell by Karen Glass

Start Here, a Journey through Mason’s 20 Principles by Brandy Vencel

Philosophy of Education by Charlotte Mason

Home Education by Charlotte Mason

Share this post